When documenting use cases for a software product, some product managers specify ones such as:

Recall that use cases represent functional requirements insofar as they convey user goals. In the example above, users enter and view information about employees. But what is the user's goal? Why on Earth would anyone want to enter information about an employee?

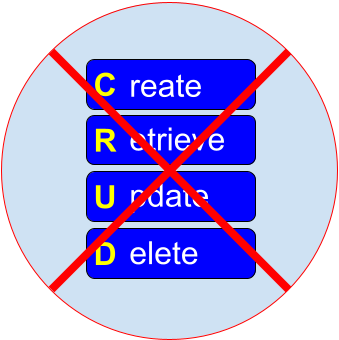

Users actually don't want to enter such information. The user wants the information to be accurate and up to date and probably to be able to examine it. But creating, updating, and deleting employees is a burden to the user. A fantasy solution would obviate the need for the user to enter such information. Therefore, the Create Employee, Update Employee, and Delete Employee use cases are not requirements and need not appear in requirements documents.

Enabling users of a product to perform CRUD functionality is sometimes the most realistic design choice. Specifying such a design in terms of use cases is helpful. However, chances are that the appearance of CRUD in a requirements document suggests your product manager doesn't understand the distinction between requirements and design.

Create EmployeeSuch functions are called "CRUD" use cases. If your product manager is specifying CRUD use cases in market requirements documents, your product manager probably doesn't understand requirements.

Retrieve Employee

Update Employee

Delete Employee

Recall that use cases represent functional requirements insofar as they convey user goals. In the example above, users enter and view information about employees. But what is the user's goal? Why on Earth would anyone want to enter information about an employee?

Users actually don't want to enter such information. The user wants the information to be accurate and up to date and probably to be able to examine it. But creating, updating, and deleting employees is a burden to the user. A fantasy solution would obviate the need for the user to enter such information. Therefore, the Create Employee, Update Employee, and Delete Employee use cases are not requirements and need not appear in requirements documents.

Enabling users of a product to perform CRUD functionality is sometimes the most realistic design choice. Specifying such a design in terms of use cases is helpful. However, chances are that the appearance of CRUD in a requirements document suggests your product manager doesn't understand the distinction between requirements and design.

Comments