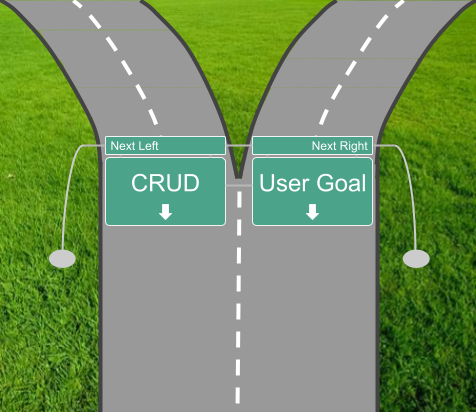

So if CRUD use cases don't belong in requirements documents, what use cases do you include in their place?

First, I should reiterate that CRUD use cases may still be appropriate outside of a requirements document, such as in a design specification. As I've mentioned, once a use case author begins fleshing out text use cases with steps, she is engaging in design, anyway.

Second, when a product manager is tempted to include CRUD in a requirements document, he should instead specify the user's larger goal. Presumably, information somehow needs to get into the system and stay up to date. Why? What does having that information enable the system to do for the user? An example of a larger goal is Generate Periodic Financial Reports. In that example, the user doesn't want to enter information; she just wants her reports!

Second, when a product manager is tempted to include CRUD in a requirements document, he should instead specify the user's larger goal. Presumably, information somehow needs to get into the system and stay up to date. Why? What does having that information enable the system to do for the user? An example of a larger goal is Generate Periodic Financial Reports. In that example, the user doesn't want to enter information; she just wants her reports!

The product manager still has to capture nonfunctional requirements relating to the accuracy and timeliness of information in the system. A useful approach is to have the use cases represent on-going, end-to-end processes instead of discrete tasks the user performs. That way they encompass the nonfunctional requirements and any data administration that product designers decide to include in their design.

For example, consider a Pay Employees use case that encompasses not just one round of payroll, but the process of paying employees during the lifetime of the company. Such a process contends with the hiring and firing of employees, and changes to employee titles, salaries, and marital status. Attach nonfunctional requirements to the use case that constrain the accuracy and timeliness of the information and limit the amount of time and effort users are engaged in carrying out the process (including the administration of information).

First, I should reiterate that CRUD use cases may still be appropriate outside of a requirements document, such as in a design specification. As I've mentioned, once a use case author begins fleshing out text use cases with steps, she is engaging in design, anyway.

The product manager still has to capture nonfunctional requirements relating to the accuracy and timeliness of information in the system. A useful approach is to have the use cases represent on-going, end-to-end processes instead of discrete tasks the user performs. That way they encompass the nonfunctional requirements and any data administration that product designers decide to include in their design.

For example, consider a Pay Employees use case that encompasses not just one round of payroll, but the process of paying employees during the lifetime of the company. Such a process contends with the hiring and firing of employees, and changes to employee titles, salaries, and marital status. Attach nonfunctional requirements to the use case that constrain the accuracy and timeliness of the information and limit the amount of time and effort users are engaged in carrying out the process (including the administration of information).

Comments

As my post suggests, I would express the larger functional requirement as an on-going, end-to-end use case. (I would just give the name of the use case, the actor, and any needed explanation. A use case diagram with notes often suffices) Then I would attach constraints to that functional requirement.

If I considered it important to convey the fact that CRUD-style administration would likely be part of the design, I would depict some use case "composition". For example, I might show that the Pay Employees use case includes a Manage Payroll use case, which in turn includes CRUD use cases. But I would explicitly label these lower-level use cases - and the <<include>> relationships - as a design example or suggestion.

Ideally, a product designer or architect documents these use cases instead.