As I mentioned yesterday, when you divide a use case into versions and distribute them among iterations, you can divide them along feature lines or requirements lines. When you divide use cases into versions along requirements lines, you relax certain constraints (nonfunctional requirements metrics) that are attached to the use case. Your team implements the most relaxed version in the first iteration. The team then implements progressively more stringent constraints in each succeeding iteration, culminating in a final iteration in which they implement the original, unrelaxed constraint.

As I mentioned yesterday, when you divide a use case into versions and distribute them among iterations, you can divide them along feature lines or requirements lines. When you divide use cases into versions along requirements lines, you relax certain constraints (nonfunctional requirements metrics) that are attached to the use case. Your team implements the most relaxed version in the first iteration. The team then implements progressively more stringent constraints in each succeeding iteration, culminating in a final iteration in which they implement the original, unrelaxed constraint.Imagine a use case for your product is to maintain a comfortable temperature. Some of the associated nonfunctional requirements are usability constraints limiting the amount of time and effort it takes for a user to achieve this goal. Yet it could be that the functionality - not the usability - is the most challenging and risky requirement for developers to implement.

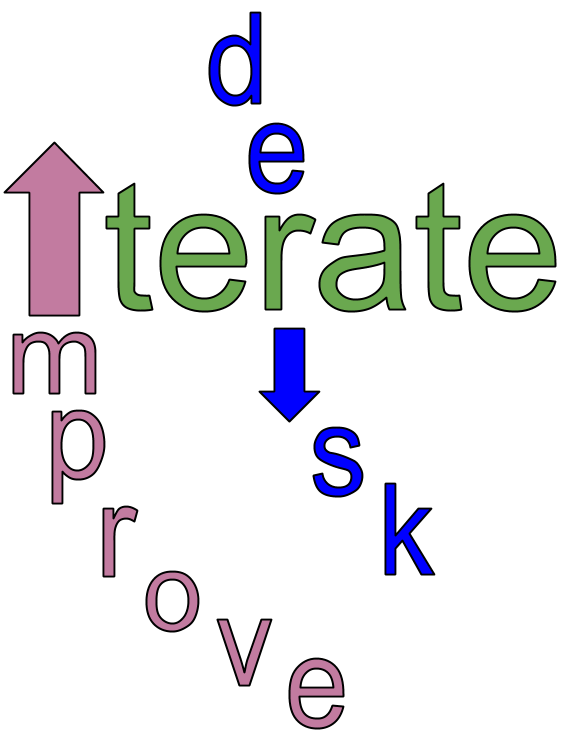

To enable the developers to implement a version of the use case in the first iteration, you can relax the usability constraints so they can focus on the functionality. As they iterate, the developers progressively incorporate the more stringent constraints:

Maintain Comfortable Temperature (low usability)Keep in mind that the purpose of iterating is to accommodate change. You should expect the use case versions in the iteration plan to change as you learn from early iterations. Sometimes these changes will be as simple as tweaking the stringency of the constraints. In other cases, you may have to take the more serious step of relaxing other constraints or deferring the implementation of use case versions further in the iteration cycle.

Maintain Comfortable Temperature (medium usability)

Maintain Comfortable Temperature (high usability)

Comments